The Moral Circle, Suffering, and Artificial Suffering

I recently reread part of Animal Liberation and The Expanding Circle, both by Peter Singer. Centered (broadly) on the idea that humans ought to extend moral patienthood to a broader set of sentient beings, the texts, published in 1975 and 1981 respectively, are especially relevant today. Disease and mutilation continue to characterize one the world’s largest vehicles of suffering — the factory farm — not to mention second-order effects including AMR resistance, deforestation and climate change. Meanwhile developments in artificial intelligence call into question what was previously unimaginable outside cinema fiction: the extension of rights and moral patienthood to sentient AI systems. In the following paragraphs, I hope to distill a few takeaways and some of my own reflections on such ideas.

Animal Liberation is widely regarded as the philosophical backbone of the animal rights / veganism movements. Singer offers a compelling defense of non-human animals by questioning the grounds upon which rights are granted. Why ought women have the right to vote? Why should Blacks obtain equality? Why don’t we have the right to torture and kill nonhuman animals for their flesh and secretions? Singer posits that while the basic principle of equality doesn’t require identical treatment, it requires equal consideration.

“It is an implication of this principle of equality that our concern for others and our readiness to consider their interests ought not to depend on what they are like or on what abilities they may possess… the basic element — the taking into account of the interests of the being, whatever those interests may be — must, according to the principle of equality, be extended to all beings, black or white, masculine or feminine, human or nonhuman.”

Singer proceeds to quote Jeremy Bentham, the utilitarian philosopher, who frames the capacity for suffering as the vital feature that gives rise to the right to equal consideration. The capacity for suffering and enjoyment is a “prerequisite for having interests at all”; “if a being suffers there can be no moral justification for refusing to take that suffering into consideration.” Just as the racist and sexist violate the principle of equality by giving preference to interests of their own group, “speciesists”, as Singer coins, engage in such moral abhorrence in relation to other species: “The pattern is identical in each case.”

In The Expanding Circle, Singer further illustrates how the arc of history bent towards justice for slaves, for women, for immigrants, to characterize the blatant ignorance of previous generations in perpetuating, just as we are with regard to non-human animals, a moral catastrophe. A good explanation on how we might be perpetuating an ongoing moral catastrophe can be found here.

Singer’s arguments are compelling, but here, two important ideas are noted: one philosophical, the other, practical.

Singer’s minimalist conception of preference utilitarianism relies on the capacity for suffering as its core premise. While the simplicity of the argument makes it attractive, it is disputed by other philosophies and philosophers like Raymond G. Frey, who contends that the key issue should be less about suffering, but about the “comparative value of lives” (still utilitarian in nature but with a difference in its emphasis). Others use non-utilitarian arguments to reject Singer’s argument by describing the key distinctions between humans and non-humans (e.g., humans hold a far greater degree of emotional / moral complexity). Ultimately, what and how we subscribe to particular philosophies determine our reception to arguments like Singer’s.

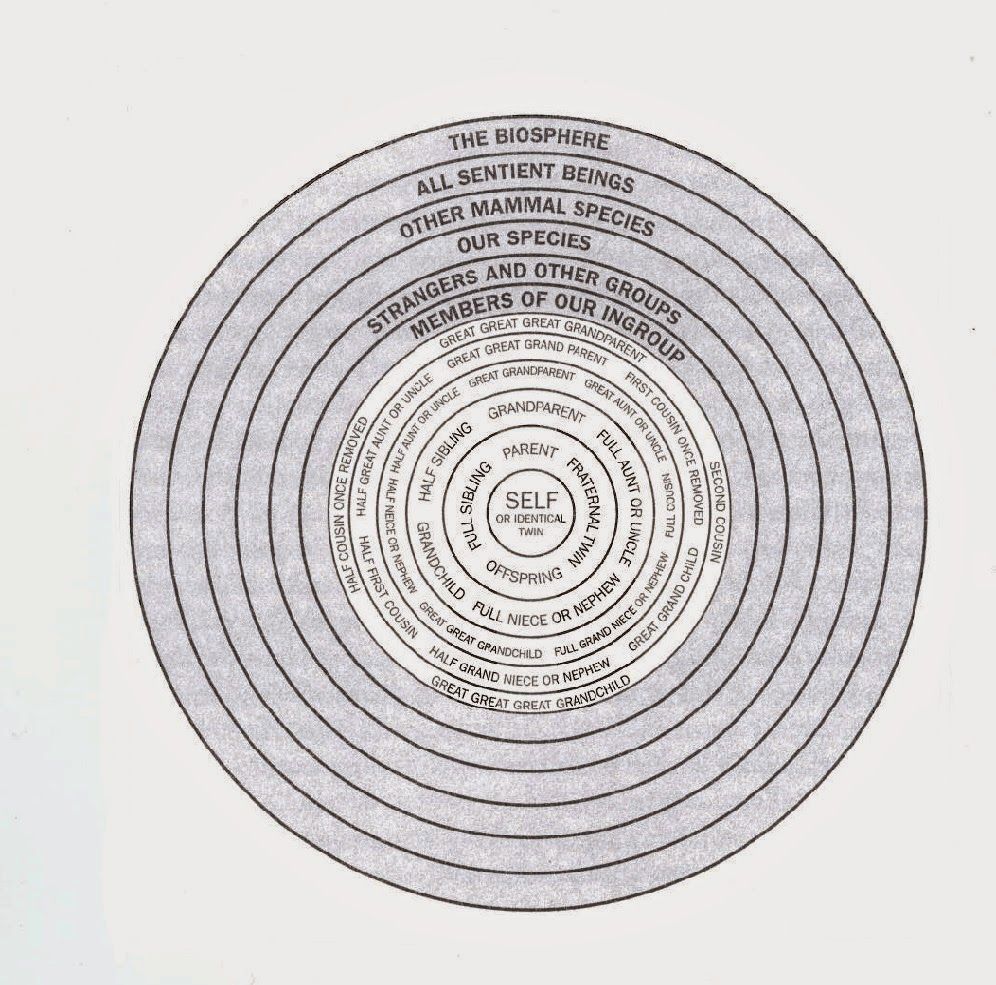

Realizing Singer’s arguments in a world of inherently fragmented identity groups (in the broadest sense of the term), be it race, nationality, or lived experiences, is virtually impossible. The moral circle has expanded, but to what degree and intensity? Is it wrong for a British to donate their income to solving domestic poverty although we know that, per dollar, their donation could achieve much more in Sub-Saharan Africa? We abhor racism and sexism on the grounds that racial and sexual distinctions are arbitrary in nature. How do we do the same for factors arguably as arbitrary as national borders in a world framed by state-centrism and community-based identities?

Two years ago, Thomas Metzinger, a German philosopher, released a paper titled “Artificial Suffering: An Argument for a Global Moratorium on Synthetic Phenomenology.” The paper calls for a global moratorium on research that could lead to the emergence of artificial consciousness until 2050. With the arrival of AGI on the horizon, the fear is that AI development will reach a stage such that AI systems might develop the ability to suffer (hence “artificial suffering”). As Metzinger writes, “On ethical grounds, we should not risk a second explosion of conscious suffering on this planet” (the first being the development of complex nervous systems via biological evolution).

The expansion and contraction of humanity’s moral circle with knowledge, technology and time will have large welfare consequences. A keen awareness of our moral philosophies, cognitive biases, and practical limitations will make us better agents of change — for fellow humans, and the countless moral patients in our midsts.